This article originally appeared in C100 on June 24, 2020.

Since C100’s founding 10 years ago, our community has had the honour of both cheering on and participating in the remarkable transformation of Canada’s technology industry. If the last few years are any indication, Canada is poised to one day assume its place as the top destination globally for talent and for entrepreneurship.

Together with some of C100’s key partners, we have summarized the rapid evolution of Canada’s dynamic innovation economy here. It is not exhaustive, but does cover the reasons why our community has so passionately pursued the mission to support, inspire, and connect Canadian entrepreneurs to capital, talent, and ideas in our home base of Silicon Valley.

The momentum is motivating. We’re proud to be part of the story. And we hope global Canadians everywhere are proud to help share Canada’s story with us.

But as we reflect on the progress of the past decade, we also find ourselves in a time of great uncertainty, rife with risks and challenges business leaders and policymakers are only just beginning to understand. With the gains made the last decade and the engagement of our whole ecosystem — industry, entrepreneurs, academia, government, and the force of Canadian talent including our “unofficial ambassadors,” those Canadians living abroad — the next decade should be one of unprecedented leadership for Canadian technology on the world stage.

I. Canada experienced ten years of unprecedented growth in its technology ecosystem, closed out by a record-shattering 2019

1. Canadians should be highly optimistic about their ability to attract venture capital — a driving force of the tech industry — given the hyper-growth in investment activity

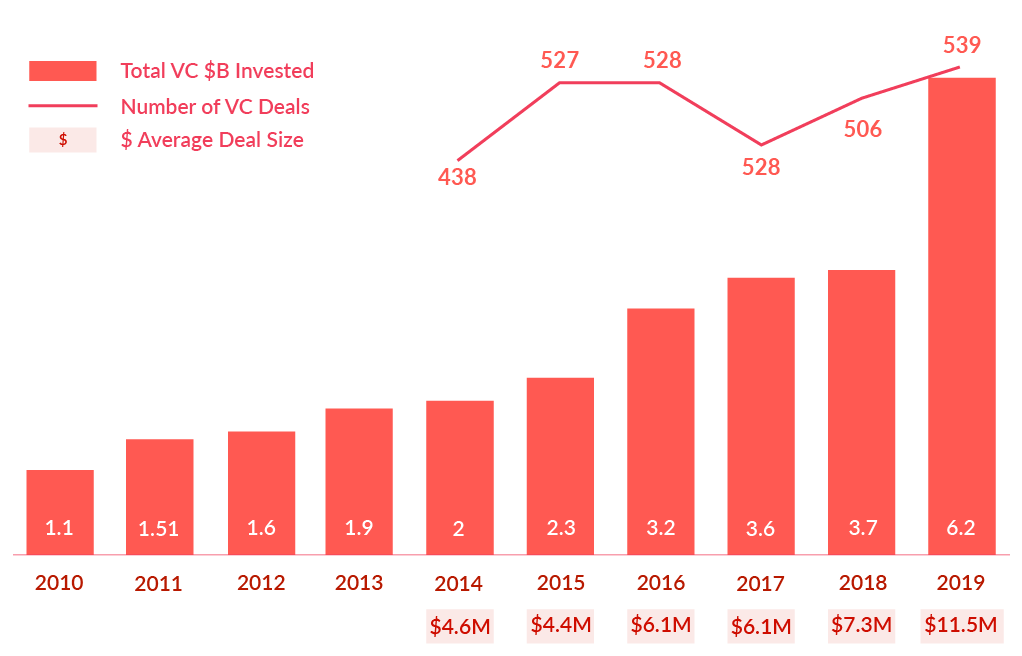

Canada experienced ten years of unprecedented growth in its technology ecosystem, closed out by a record-shattering 2019. The past five years have seen sustained year-over-year growth in venture capital (VC) investment into Canadian technology companies on all metrics: total dollars invested, the number of deals, and average deal size (which has more than doubled). In 2019, the volume of VC invested in Canada had its greatest uptick ever with 40% growth over the previous year.

Figure 1. Total VC investment and deal count in Canada, C$ billions, per annum. Source: CVCA, BDC Capital.

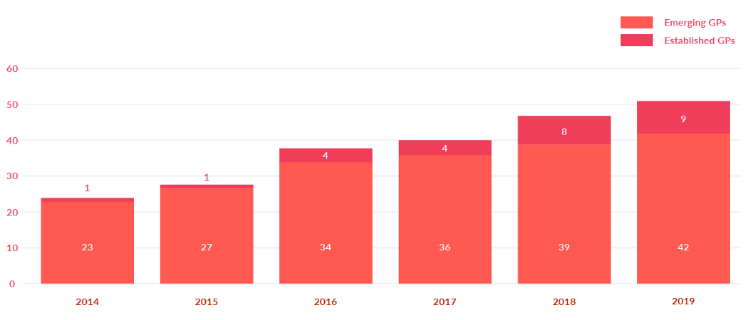

The sector’s growth is also reflected in the number of active Canadian General Partners (GPs) which has doubled over the past five years, driven both by emerging and established funds. The number of new “emerging” GPs (fund 1–3) has increased from 23 to 42, and “established” GPs (fund 4+) from 1 to 9.

Figure 2. Total number of active Canadian GPs with fund sizes exceeding $10M, 2014–2019. Source: BDC Capital.

What’s more: the presence of large funds has also grown significantly. At the end of 2014, there were just 3 funds exceeding $100M, compared to the now 14 funds. Over the past five years, the average size of these funds has grown 52%, from $136M in 2014 to $207M in 2019. Often cited as a cardinal challenge for high-growth companies, access to growth capital for later financing rounds is more accessible today, thanks in part to the presence of larger Canadian funds.

Investments from top-tier U.S. funds are no longer an anomaly in Canada many of the best VC firms like Accel, Bessemer, a16z, GGV in the U.S. (to name a few) and the top corporate VCs have now made Canadian investments and have an appetite for more. And we’re seeing more US-based LPs investing into Canadian VC and growth equity firms.

— Win Bear (Head of BD Canada, Silicon Valley Bank)

The Canadian VC sector has emerged as a major global contender. Five- and ten-year investment returns (the measure of performance in the VC asset class) in Canada has seen a dramatic improvement, compared to their American counterparts. Canadian VC ten-year returns crossed the 5% hurdle in 2018, and are closing the gap with U.S. VC. Today, Canada lags only the U.S. and Israel for the relative size of its VC industry, representing 0.16% of Canada’s GDP (compared to 0.55% in the U.S.).

Figure 3. VC returns in Canada and the U.S., 2013–2018 (%). Source: BDC Capital, Cambridge Associates.

2. Canada has emerged as a creator of and destination for global talent

Canada is making itself home for a new wave of ambitious entrepreneurs and technology companies attracted by a diverse, highly-educated talent pool and favourable immigration policies. The success of Ottawa-based e-commerce titan Shopify is heralded as Canada’s current-day quintessential talent magnet and in recent weeks has become Canada’s most valuable company in any sector, at a $121B market capitalization. Coming up from behind Shopify, many of Canada’s most promising technology companies have been founded by Canadians returning home after experiences in Silicon Valley, such as Andrew D’Souza of Clearbanc, Ray Reddy of RITUAL, and Michael Katchen of Wealthsimple, to name a few.

Citing the depth of technical talent and world-class universities, iconic global players are making moves north, and their investments are driving substantial job gains. In Q4 of 2019, Amazon announced its plan to create 10,000 jobs in Vancouver. Google and Apple made similar announcements for 5,000 jobs in cities including Montreal, Kitchener-Waterloo, Hamilton, and Vancouver, while Uber announced an investment of over $200M in Toronto over five years for its new self-driving engineering hub.

Over the past five years, 80,000 new tech jobs have been created in Toronto alone, more than San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. combined. Other Canadian cities are emerging hotbeds of talent, too. Of the major cities in North America, Vancouver demonstrated the greatest year-over-year gains with 43% growth in tech jobs. Ottawa is tied with the SF Bay Area to lead North America in tech talent concentration at 10%, three times the Canadian average. The growth is not just concentrated in big cities: Hamilton and Waterloo are two of the fastest-growing “opportunity markets” in North America with 52% and 40% growth respectively in tech job creation.

Canada has been responsive to the needs of the growing tech sector with progressive immigration policy, doubling down every time the U.S. pulls back on immigration. Canada now welcomes five times the number of skilled immigrants as a percentage of its population than does the U.S. The Global Talent Stream visa program launched in 2017 promises easy entry for international technical hires in as little as 10 business days, and the private sector is quick to react. Half of the immigrants admitted into Canada over 2018 held a STEM degree. Notably, 65% of U.S. tech HR professionals surveyed by Envoy view Canada’s immigration policy as more favourable than that of the U.S., and 35% envision sending more of their workforce to Canada and boosting hiring foreign nationals to work there.

Figure 4. Skilled foreign workers as a percentage of the total population, 2013–2018. Sources: Government of Canada, U.S. Department of State, Statistics Canada, U.S. Census Bureau.

In the opposite direction, Canadians abroad may be motivated to learn that Canadian-headquartered companies are aggressively growing their own international presence, particularly into the next-door market. Nearly two-thirds of international hiring by Canadian tech companies in 2019 was in the U.S. There are emerging priority regions: including Europe (20%) and Asia (11%).

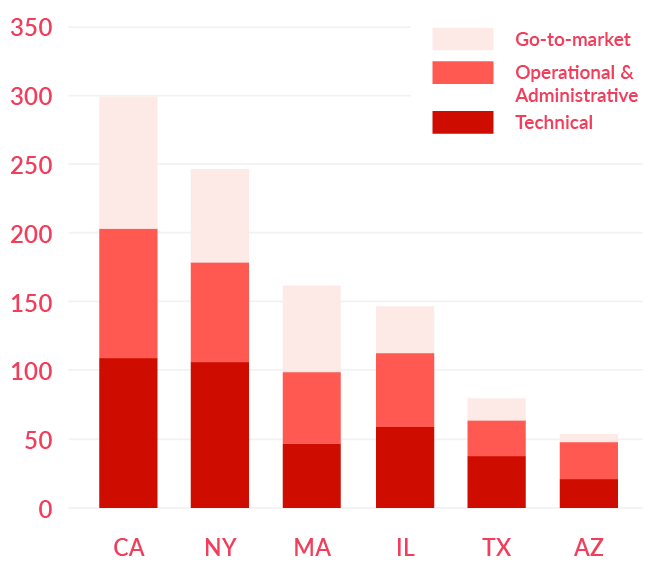

Figure 5. Breakdown of Canadian-headquartered startup jobs located in six most common U.S. states, 2019. Source: Prospect.

Unlike domestic hiring which tends to focus on technical roles, the majority of hiring in the U.S. and Europe is in ‘go-to-market’ functions such as marketing, sales and business development and operations. However, the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic downturn have taken a toll as hiring trends both at home and abroad for Canadian companies plunged by 60% from January to April, 2020. There is still reason to be optimistic — even after a challenging quarter, over 12,000 open job postings remain active at Canadian startups.

II. There are still hurdles that the Canadian tech ecosystem must clear to benchmark against the U.S.

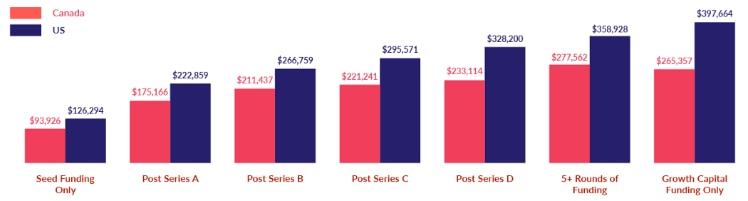

1. Venture-backed businesses in Canada are still less capitalized than U.S. counterparts.

On average, startups in Canada raise less than half as much VC than do American companies, with the median pre-exit capital raised at $6.8M, compared to $15.8M in the U.S.

Lastly, even though larger and later-stage funds are a growing presence in Canada, some late-stage funding gaps persist, showing there is still room for additional late-stage capital to support the country’s highest-growth companies.

Given that only a few large exits in a VC portfolio often drive an entire fund’s return, it is critical for Canada to achieve higher exit values. 2019 was a record year for Canadian VC-backed exits and Lightspeed’s IPO earlier this year is proof that Canadian companies can remain in Canada and still reach billion-dollar valuations.

— Thomas Park (Vice-President of Operations and Strategy at BDC Capital)

2. Executive talent is still wooed by higher salaries and bigger exits south of the border

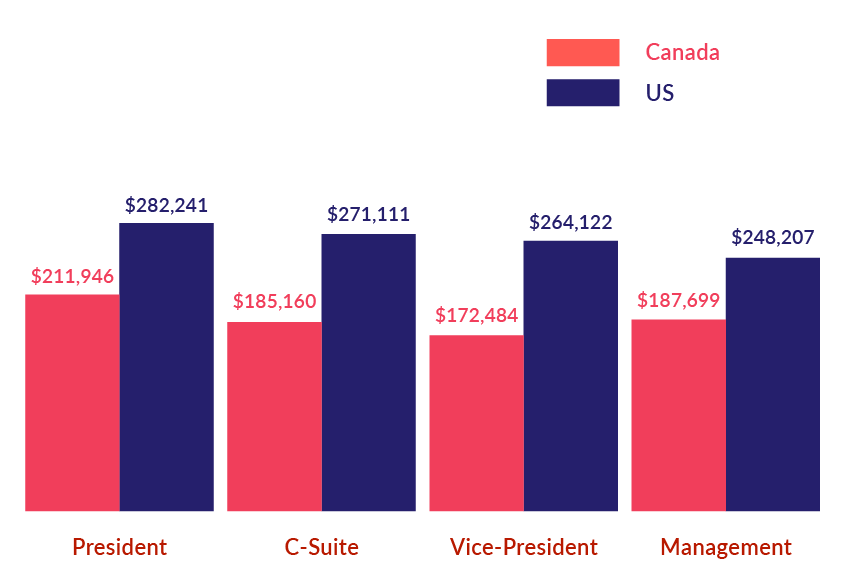

CEOs and founders in Canada share that access to executive “scaling” talent remains a cardinal challenge. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, research conducted by the BDC offers one possible explanation for that challenge: compensation. Canadian tech executives earn on average $87,000 USD less than their colleagues in the U.S. earn. This gap persists at every funding stage and in every sub-sector, and across all senior leadership ranks. We are unsure of how the pandemic will impact compensation going forward, but drawing attention to recent trends may shed light on the opportunity.

Figure 6. Average tech executive compensation in VC-backed firms per position, 2018, $USD. Source: BDC Capital.

Figure 7. Average tech executive compensation in VC-backed firms per funding round, 2018, $USD. Source: BDC Capital.

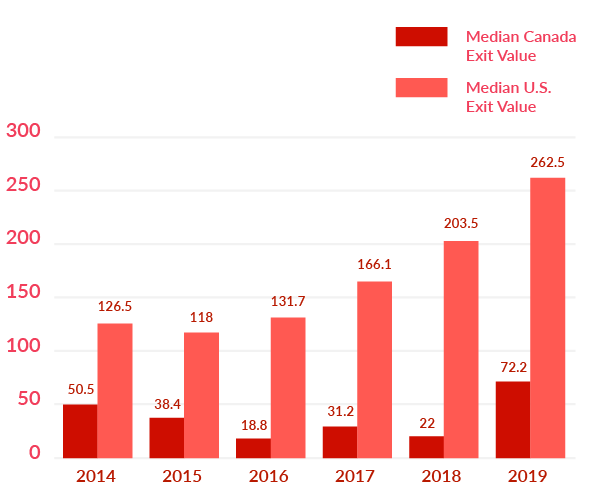

Despite salary gaps, Canadian companies are actually quite competitive when it comes to equity-based compensation. But, median exit values in Canada significantly lag the U.S., thus it is far from enough to bridge the gap.

Figure 8. Median VC exit value in Canada and the U.S., C$ millions, 2014–2019. Source: BDC Capital.

There are a number of factors likely responsible for the compensation gap:

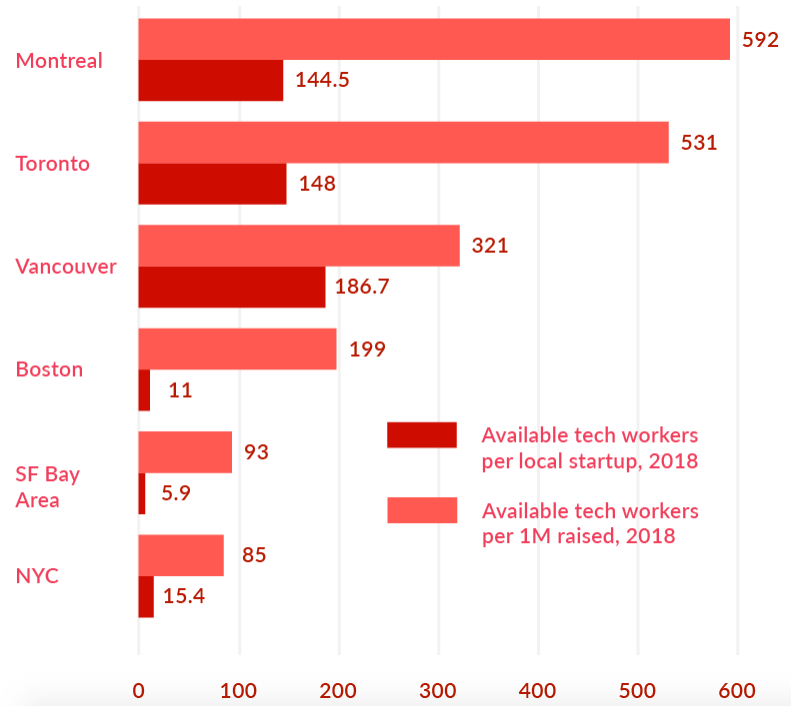

First, is an issue of supply and demand: Canadian cities are home to more tech workers per firm and more newcomers than major American tech hubs, meaning the labour market in Canada is simply not as tight, thereby pressuring wages upward in the U.S.

Figure 9. Benchmark of available tech workers in major Canadian and U.S. cities, 2018.

Second, U.S. companies boast a greater concentration of talent with advanced tech degrees, even though proportionally Canada produces more STEM graduates. “Pedigree” demands higher salaries.

Lastly, Canada’s talent compensation is still benchmarked regionally, which investors use to set compensation estimates when investing. Locally attractive salaries might not be enough to recruit executive talent out of U.S. hubs, where the most ambitious firms are willing to pay for top talent.

Are Canadians with high earning potential simply choosing other industries? Or are those same workers moving abroad? Whatever the cause, American companies are outcompeting Canadian ones for executive talent, and the lure of opportunity down south has pounded a well-trodden path for Canadians seeking higher earnings and bigger outcomes.

III. Canada’s track record of resilience leaves us destined for new opportunities

Times are undeniably tough right now. The economy is anticipated to shrink at an annualized rate of 25% in the second quarter of 2020 and as many as 2.8M jobs may be lost. Startups are hiring less (job postings have decreased by one-third), and three-quarters of companies report the intention to scale back hiring to accommodate a looming recession. Nearly two-thirds of startups are conducting layoffs, amounting to 5% of Canada’s startup workforce. Anecdotes circulate of executive teams reducing or completely eliminating their own salaries to try to keep teams (and morale) intact.

Canada’s competitive advantage is our flexible, dynamic and well-educated labour force, consistently ranking among the leaders of the OECD group of countries in terms of education attainment. Moving forward, we are well-positioned to take full advantage of an economy that will tilt to brains over brawn. To take full advantage of these accelerating trends, however, we need businesses and investors to ramp up R&D in the emerging sectors to provide the tools necessary for the workforce of today to be ready for the economy of the future.

— Craig Wright (Chief Economist, RBC)

Investment activity into startups has also slowed down in 2020. VC investment in Q1 of 2020 ended at $834M, the first decline after three successive quarters exceeding $1B. Nearly 70% of startups in Canada reported during the COVID-19 pandemic that their fundraising prospects have been negatively impacted by the crisis, with 40% deciding to postpone fundraising to a later date to better their odds.

The macro-risks facing Canada’s tech ecosystem are no less daunting. One potential risk is that foreign investment into Canada may dwindle as sovereign wealth funds and other institutional investors pull back. In addition to being a major source of capital for Canadian VCs, foreign capital also represents between one-third and one-half of investment in Canadian companies, with the U.S. being the leading source of international investment.

Purchasing activity is also expected to slow down, stalling the growth of our scaling startups. A May 2020 CIBC equity analyst report forecasted a significant decrease in IT spending in 2020 which “runs counter to much of the commentary on Q1 earnings calls from the software providers.” Declines are predicted across most IT segments, but cloud software may see a boon: “As organizations have been forced into embracing remote work, the importance of nimble, accessible infrastructure and a clear digital strategy have been made evident.”

VC returns and liquidity may also suffer, threatening capital availability and thereby the near-term outlook of the industry as a whole. Threats to the VC industry may be amplified by less capital from high net worth (HNW) individuals, family offices and corporate venture capital (CVC), and other sources of alternative capital being injected into the industry. Cash-strapped startups in more hard-hit sectors (such as travel, mobility, hospitality, live entertainment, real estate) may struggle to stay afloat, which will challenge investors with too much exposure in these sectors within their portfolios.

But, we have seen in the past a world of uncertainty can offer outsized opportunities for Canada.

As the world shifts from “growth at all costs” to “path to profitability” and a focus on metrics, the Canadian companies and entrepreneurs forced to do more with less should easily transform into by-the-numbers’ superior companies. Proximity matters less and less as a result of COVID; Canadian companies should now feel emboldened. To be sure, COVID has caused dislocation and the need to rethink value propositions, but we are still in the early innings of global digitization. It is essential our entrepreneurs continue to tackle difficult problems, think globally and leverage Canada’s powers of attraction as it relates to immigration and culture. We are poised to succeed.

— David Rozin (Vice President and Head, Technology and Innovation Banking, Scotiabank)

As talent becomes more distributed, Canadian companies that thrive in this “new normal” will be better positioned to compete for global talent — whether that talent finds its way into the Canadian borders or not. After the pandemic, the workforce may look very different and Canada may need to accelerate its reskilling of the population to fit the needs of the emerging economy. Our aptitude to do so may very well position Canada as a model globally.

For the better part of the past century, Canadian expats have been quietly inserting themselves into pretty much every significant movement, from international human rights to global media, usually excelling with those common Canadian — and globally rare — attributes of empathy, balanced thinking and reasonable accommodation. In few sectors is this more evident than technology, where Canadians can be found almost everywhere, with a combination of tech skills and human skills. A divided, distanced world will need these bridge-builders even more. And Canadian foreign policy — challenged anew by a fractured world — can harness them for our country’s strategic advantage.

— John Stackhouse (Senior Vice President, Office of the CEO, RBC), from his upcoming book Planet Canada: How our Expats are Shaping the Future.

Talent-based immigration is a core competency for Canada, and an opportunity to double down its position globally. As the U.S. consistently closes channels to immigration, will Canada continue its pattern of opening up? In an economy where one of five tech workers is foreign-born, Canada may very well be the place the next generation of entrepreneurs and operators choose to make home.

What is the call to action? Canada’s expat community and diaspora network can play a key role in propelling our nation forward: it’s about the power of people and community.

Co-authored by: Laura Buhler & Joshua Goodfield of the C100, with contributions from David Rozin (VP & Head, Technology and Innovation Banking, Scotiabank), Thomas Park (VP, Operations & Strategy, BDC Capital), Charles Lespérance (AVP, Ecosystem Development, BDC Capital), John Stackhouse (SVP, Office of the CEO, RBC), Marianne Bulger (Founder & CEO, Prospect), Craig Wright (Chief Economist, RBC), Martin Philipp (Senior Manager, Operations Support VC, BDC Capital), Win Bear (Head of BD Canada, Silicon Valley Bank), and Paul McKinlay (Managing Director, CIBC Innovation Banking).